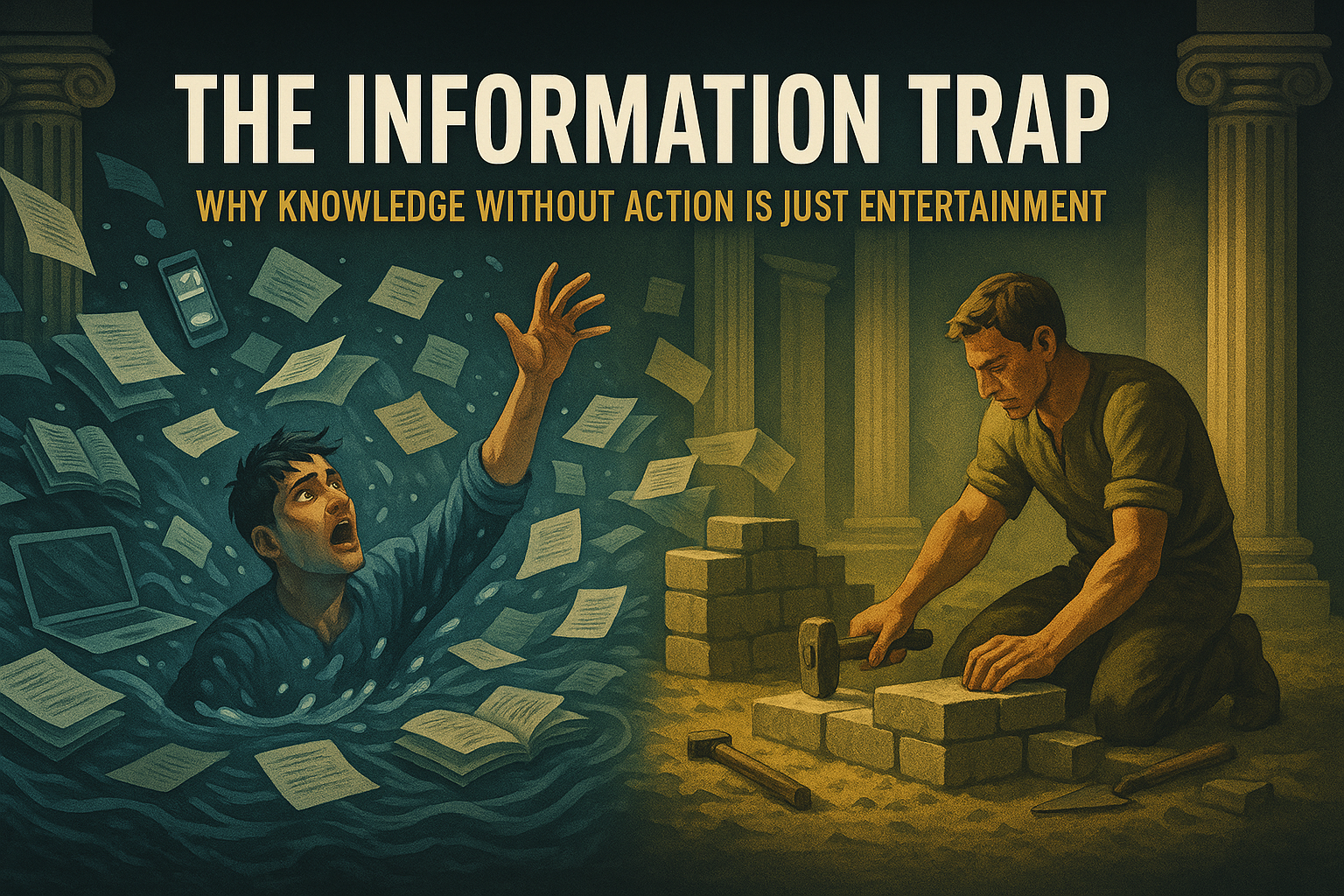

The Information Trap: Why Knowledge Without Action Is Just Entertainment

By Derek Neighbors on June 21, 2025

I caught myself red-handed last Tuesday.

There I was, bookmarking another “10 Habits of Highly Effective Leaders” article while my own team was struggling with a decision I’d been avoiding for weeks. I had a browser full of tabs about “productivity hacks” while my most important project sat untouched. I was consuming content about “taking action” instead of actually taking action.

I was addicted to the illusion of learning.

And I wasn’t alone. We live in the golden age of information, where knowledge is more accessible than ever before. We can learn anything, anytime, anywhere. So why are we not getting proportionally better at what we do? Why does more information often lead to less action?

Because most of what we call “learning” is actually entertainment in disguise.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Information without action is intellectual hoarding, not growth. It’s the mental equivalent of buying exercise equipment and never using it, collecting recipes and never cooking, or downloading language apps and never practicing conversation.

We’ve confused consuming insights with developing capabilities. We’ve mistaken information gathering for skill building. We’ve turned learning into a performance instead of a practice.

The Greeks had a word for this trap, and a way out of it.

The Consumption Delusion

Let’s start with some brutal honesty about modern “learning” culture.

How many articles have you read about leadership in the past month? How many podcasts have you listened to about productivity? How many videos have you watched about entrepreneurship or personal development?

Now, how many of those insights have you actually implemented? How many of those frameworks have you put into practice? How many of those strategies have you tested in the real world?

If you’re like most people, the ratio is somewhere around 100:1 consumption to implementation.

This isn’t a personal failing; it’s a systemic problem. We’ve created an entire economy around information consumption. Social media algorithms reward us for engaging with content, not for applying it. The self-help industry profits from keeping us consuming, not from helping us implement. Educational platforms measure success by completion rates, not by real-world results.

The modern world has turned learning into a spectator sport.

Think about it: Reading about leadership feels productive. Listening to podcasts about success feels like progress. Watching videos about entrepreneurship feels like preparation. But none of these activities actually develop capability. They create the illusion of advancement without the reality of improvement.

This is the consumption delusion: confusing information intake with skill development.

The delusion is reinforced by our social media culture, where sharing insights gets rewarded more than implementing them. You get more likes for posting a quote about hard work than for actually doing hard work. You get more engagement for sharing a framework than for applying it.

We’ve gamified learning in a way that rewards consumption over creation.

The result? We have a generation of people who know more about success than any generation in history, but who struggle to implement what they know. We have access to the wisdom of ages, but we treat it like entertainment rather than instruction.

Information without implementation is just intellectual entertainment.

Praxis vs. Theory: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Problems

The Greeks understood something we’ve forgotten: There’s a fundamental difference between knowing something and being able to do something.

They had two concepts that perfectly capture this distinction: episteme (theoretical knowledge) and praxis (practical action). episteme is knowing that fire is hot. Praxis is knowing how to build a fire, tend it, and use it to cook food.

Modern culture has become obsessed with episteme while neglecting praxis.

The Greeks also had a concept called phronesis, often translated as “practical wisdom.” This wasn’t wisdom you could get from books or lectures. It was wisdom that came from experience, from making decisions under uncertainty, from dealing with real consequences in real situations.

You can’t develop phronesis through consumption; you can only develop it through action.

Aristotle was clear about this:

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

Notice he didn’t say, “We are what we repeatedly read about” or “We are what we repeatedly think about.” He said we are what we repeatedly do.

Excellence is a practice, not a theory.

This is why business schools struggle to create entrepreneurs. They can teach the theory of entrepreneurship, but they can’t teach the praxis of it. They can explain market analysis, but they can’t simulate the experience of making payroll when cash is tight. They can discuss leadership principles, but they can’t replicate the feeling of making a decision that affects people’s livelihoods.

The most important lessons can only be learned through doing.

Consider the difference between reading about swimming and actually swimming. You can read every book ever written about swimming technique, watch every video about proper form, study the physics of buoyancy and propulsion. But until you get in the water and actually swim, you don’t really know how to swim.

Knowledge is potential; action is actualization.

The ancient Greeks valued phronesis precisely because they understood that real wisdom comes from the integration of knowledge and experience. It’s not enough to know what the right thing to do is; you have to develop the practical wisdom to do it in complex, uncertain, real-world situations.

Practical wisdom can’t be downloaded; it has to be developed through practice.

The Entertainment Trap: When Learning Becomes Performance

Here’s where the information trap gets really insidious: We’ve turned learning into a form of entertainment that masquerades as productivity.

Social media has weaponized our desire for growth. LinkedIn feeds us a constant stream of “insights” and “lessons learned” that feel profound but require no effort to consume. Twitter gives us bite-sized wisdom that makes us feel smart without making us more capable. YouTube serves up endless “how-to” content that we watch instead of actually doing.

The dopamine hit of consuming insights has replaced the satisfaction of developing skills.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Consuming content feels good and requires minimal effort. Implementing insights feels hard and requires sustained effort. So we naturally gravitate toward consumption over implementation.

We’ve become addicted to the feeling of learning without the effort of applying.

The entertainment trap is particularly dangerous because it’s socially acceptable. Nobody questions your productivity when you’re reading business books or listening to educational podcasts. It looks like professional development. It feels like growth. But if you’re not implementing what you’re consuming, it’s really just sophisticated procrastination.

Information consumption becomes a way to avoid the difficult work of actual implementation.

Think about the last conference you attended or the last online course you completed. How much of that material have you actually applied? How much of it changed your behavior or improved your results? Most people attend conferences and complete courses and then go right back to doing things exactly the same way they did before.

We’ve confused exposure to ideas with adoption of practices.

The worst part is that excessive consumption can actually inhibit action. When you’re constantly consuming new information, you never have time to implement what you’ve already learned. You’re always chasing the next insight instead of applying the last one.

Analysis paralysis is often just consumption addiction in disguise.

Action as Teacher: What Doing Teaches That Reading Cannot

Here’s the fundamental truth that the information age has obscured: Action is the best teacher.

When you actually do something, you get feedback that no book, article, or video can provide. You encounter problems that no theory anticipated. You discover nuances that no framework captured. You develop intuition that no amount of study can create.

Real-world application creates data that theoretical consumption cannot.

Let me give you a personal example. I spent years reading about leadership and management. I consumed countless books, articles, and courses about how to build teams, motivate people, and drive results. I thought I understood leadership.

Then I actually started leading a team. Within the first week, I realized that everything I thought I knew was incomplete. The real challenges weren’t in the books. The human dynamics were more complex than any framework suggested. The decisions were messier than any case study prepared me for.

The gap between knowing about leadership and actually leading is the gap between theory and practice.

This is why apprenticeships were so effective throughout history. You didn’t learn a craft by reading about it; you learned by doing it under the guidance of someone who had mastered it. You made mistakes, got feedback, and tried again. You developed skill through repetition, not through consumption.

Mastery comes from iteration, not information.

Action teaches in ways that consumption cannot:

Action teaches timing. You can read about when to have difficult conversations, but you only learn timing by having them and experiencing the consequences of good and bad timing.

Action teaches adaptation. You can study frameworks for problem-solving, but you only learn to adapt when you encounter problems that don’t fit the framework.

Action teaches resilience. You can read about overcoming obstacles, but you only build resilience by actually facing obstacles and pushing through them.

Action teaches intuition. You can learn principles of decision-making, but you only develop good judgment by making decisions and living with the results.

The feedback loop of action is what creates real learning.

When you act, you get immediate feedback about what works and what doesn’t. When you consume, you get the illusion of learning without the reality of testing. Action forces you to confront the gap between theory and practice. Consumption lets you maintain comfortable illusions.

Failure teaches faster than success stories.

When you read about someone else’s success, you get their interpretation of what worked. When you fail at something yourself, you get direct feedback about what doesn’t work. Your failures teach you more about your own capabilities and limitations than someone else’s successes ever could.

This is why the most effective learning happens at the intersection of action and reflection.

The Implementation Imperative: Converting Knowledge to Capability

So how do you break free from the information trap? How do you convert knowledge into capability? How do you become a creator instead of just a consumer?

The Implementation Imperative is a five-step framework for turning information into action:

1. Consume with Intent

Stop random consumption. Stop scrolling through feeds looking for the next insight. Stop collecting information without a specific purpose.

Every piece of content you consume should have a clear implementation goal.

Before you read an article, listen to a podcast, or watch a video, ask yourself: “What specific problem am I trying to solve?” “What skill am I trying to develop?” “How will I apply what I learn?”

Purposeful consumption is the first step toward practical application.

2. Apply Immediately

Here’s the rule that changed everything for me: If you don’t implement an insight within 24 hours, you probably never will.

The moment you consume something valuable, immediately identify one specific way you can apply it. Not tomorrow, not next week, not when you have more time. Right now.

Implementation momentum is created through immediate action, not delayed planning.

This might mean having a difficult conversation you’ve been avoiding after reading about feedback. It might mean changing a process after learning about efficiency. It might mean setting a boundary after consuming content about work-life balance.

The 24-hour rule prevents insights from becoming intellectual entertainment.

3. Measure Results

You can’t improve what you don’t measure. If you’re going to implement something, you need to track whether it’s actually working.

Create simple metrics for the changes you’re making.

If you’re implementing a new productivity system, measure your output. If you’re applying a leadership principle, measure team engagement. If you’re trying a new communication approach, measure relationship quality.

Measurement turns implementation into learning.

4. Iterate Based on Feedback

Implementation isn’t a one-time event; it’s an ongoing process of refinement. The first version of anything you try probably won’t work perfectly. That’s not failure; that’s learning.

Use feedback to improve your application, not to abandon it.

Most people try something once, encounter resistance or imperfect results, and give up. But the real learning happens in the iteration. How do you adapt the principle to your specific situation? How do you modify the approach based on what you’ve learned?

Iteration is where knowledge becomes wisdom.

5. Teach Others

The ultimate test of understanding is your ability to teach someone else. If you can’t explain how to apply something you’ve learned, you haven’t really learned it.

Teaching forces you to move from consumption to comprehension.

This doesn’t mean you need to become a formal teacher or coach. It means looking for opportunities to share what you’ve learned through application. Mentor a colleague. Write about your experience. Lead a discussion about what you’ve implemented.

Teaching others what you’ve learned through doing creates a feedback loop that deepens your own understanding.

From Consumer to Creator

Here’s the transformation I want you to understand: The goal isn’t to stop learning; it’s to start implementing.

The most successful people I know aren’t the ones who consume the most information. They’re the ones who consistently convert insights into action. They read less but implement more. They attend fewer conferences but apply more of what they learn. They follow fewer thought leaders but practice more of what resonates.

They’ve shifted from being information consumers to being value creators.

This shift changes everything. Instead of collecting insights, you start creating results. Instead of impressing people with what you know, you start influencing them with what you do. Instead of being entertained by other people’s wisdom, you start developing your own through practice.

The compound effect of implementation is exponentially more powerful than the compound effect of consumption.

When you implement consistently, you develop practical wisdom (phronesis) that can’t be found in any book or course. You build capabilities that can’t be downloaded or purchased. You create value that can’t be replicated by someone who’s only consumed the same information.

Implementation is what separates the students from the practitioners, the consumers from the creators, the talkers from the doers.

The Greeks understood this. arete (excellence) wasn’t something you could learn about; it was something you had to become through practice. eudaimonia (flourishing) wasn’t a theory you could study; it was a way of life you had to live.

Excellence is a practice, not a theory. Flourishing is an action, not an idea.

The information trap is seductive because it’s comfortable. Consumption feels like progress without requiring the risk and effort of implementation. But comfort is the enemy of growth. The path to real capability runs through the difficulty of application, not the ease of consumption.

Your transformation from consumer to creator begins with the next insight you choose to implement instead of just consume.

Final Thought

The ancient Greeks distinguished between episteme (theoretical knowledge) and praxis (practical action) because they understood a fundamental truth: wisdom without application is merely intellectual entertainment. The path to arete (excellence) has always required the courage to move from knowing to doing, from consuming to creating. In our age of infinite information, the rarest skill isn’t learning faster, it’s implementing immediately. True eudaimonia (flourishing) comes not from what we know, but from what we do with what we know.

What’s one thing you’ve been learning about but not implementing? What would happen if you applied it today instead of consuming more information about it tomorrow? The opportunity to break free from the information trap is always one action away.