Creating Environments for Excellence: The Ultimate Leadership Leverage

By Derek Neighbors on June 21, 2025

I walked into the office and immediately felt the difference.

Same company. Same industry. Same competitive pressures. But this place hummed with a different energy. People moved with purpose. Conversations sparked with genuine curiosity. Problems got solved quickly because information flowed freely. Excellence wasn’t demanded; it was the natural outcome of how everything was designed.

The CEO wasn’t barking orders or micromanaging details. Hell, I barely saw her that first day. But her influence was everywhere, woven into the systems, the space, the culture, the very DNA of how work got done.

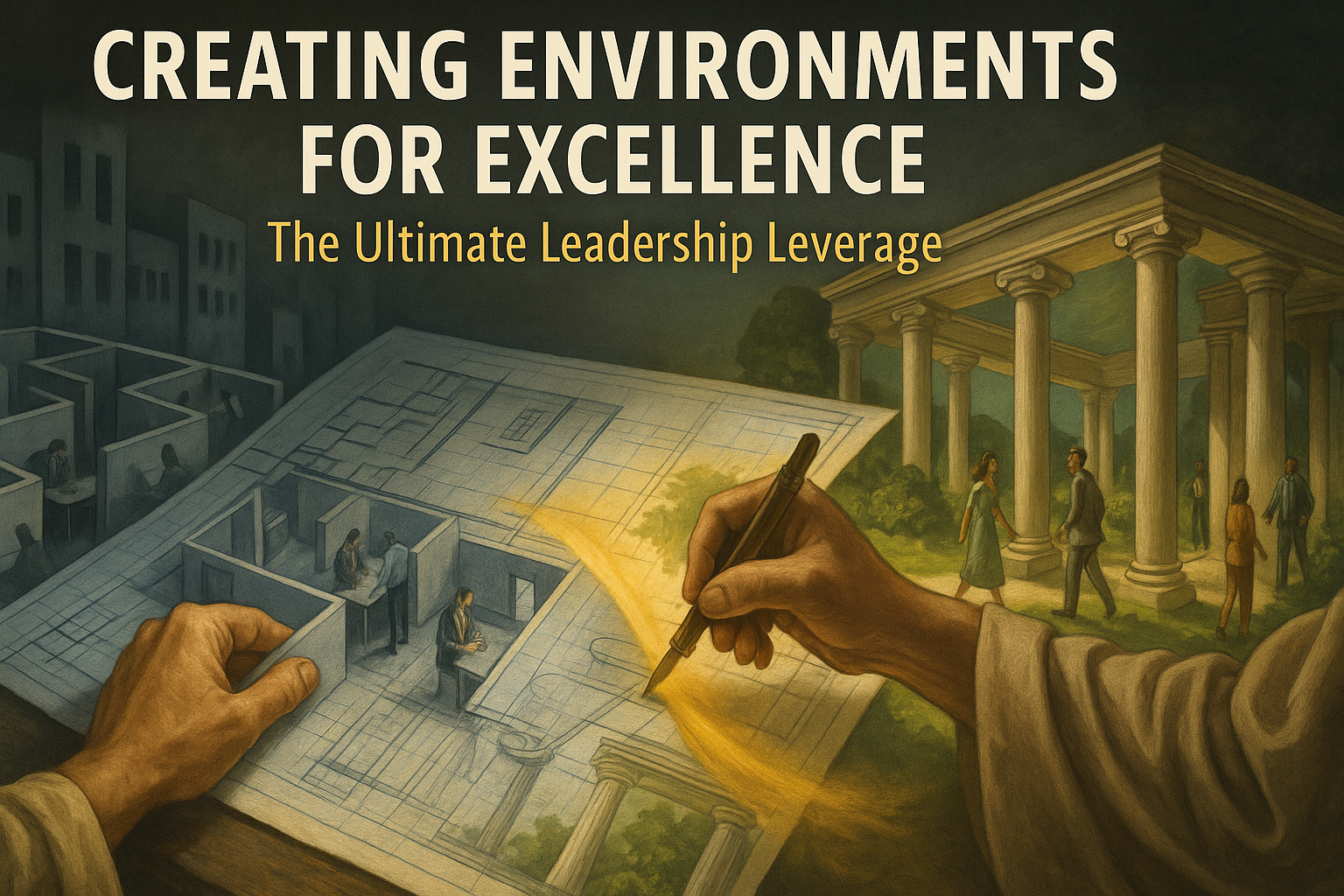

She had discovered the ultimate leadership leverage: creating environments where excellence becomes inevitable.

Most leaders exhaust themselves trying to control people’s behavior. They write more policies, hold more meetings, implement more oversight. They push harder, demand more, and wonder why their teams feel like they’re swimming upstream.

They’re solving the wrong problem.

The problem isn’t the people. The problem is the environment.

The Environment Paradox

Here’s the leadership paradox that breaks most managers: The harder you try to control people, the more they resist. The better you design their environment, the more they naturally excel.

Think about your own experience. When have you done your best work? I guarantee it wasn’t when someone was breathing down your neck, checking your every move, and questioning your decisions. It was when you had clarity about what mattered, the tools you needed to succeed, and the freedom to figure out how to get there.

Great leaders don’t manage behavior; they design conditions.

This is where most leadership thinking goes completely sideways. We focus on the person instead of the system. We try to motivate individuals instead of creating environments that naturally motivate. We attempt to control outcomes instead of designing processes that reliably produce those outcomes.

The Greeks had a concept for this: eudaimonia, often translated as “flourishing” or “the good life.” But eudaimonia isn’t about happiness or pleasure, it’s about creating conditions where human beings can express their highest potential. It’s about designing environments where excellence becomes the natural state, not the exception.

Environmental leadership is about creating the conditions for eudaimonia at scale.

Here’s what this looks like in practice: Instead of telling people to be more collaborative, you design spaces and systems that make collaboration the easiest path forward. Instead of demanding innovation, you create environments where experimentation is safe and learning from failure is rewarded. Instead of pushing for better communication, you build structures that make information sharing automatic and transparent.

The difference between managing people and designing environments is the difference between pushing a boulder uphill and creating a slope where it naturally rolls in the right direction.

Most leaders are exhausted because they’re fighting against their own systems.

The Authority Through Design Principle

In Part 1 of this series, we explored how real authority flows from character, not position. Now here’s the multiplier effect: Environmental design amplifies the authority of example exponentially.

When you lead through character alone, your influence is limited by your personal presence. You can only be in one place at a time, have so many conversations, touch so many decisions directly. But when you embed your values and principles into the environment itself, your influence scales beyond your physical presence.

Your environment becomes an extension of your leadership.

Think about Southwest Airlines. Herb Kelleher’s leadership philosophy of putting employees first didn’t just live in his personal interactions, it was built into every system, policy, and process. The hiring criteria, the training programs, the performance metrics, the physical workspace design, all of it reinforced the core values of fun, freedom, and caring for each other.

The result? Southwest’s culture continued to drive performance long after Kelleher stepped down because the environment itself had become a leadership system.

This is the Permission Principle: Well-designed environments give people permission to be their best selves.

Most organizational environments are accidentally designed to bring out people’s worst instincts. They create scarcity, competition, fear, and politics. They reward self-preservation over collaboration, short-term thinking over long-term value creation, looking good over being good.

But what if you flipped that? What if your environment was intentionally designed to bring out people’s best instincts? What if the easiest path forward was also the right path forward?

Consider Netflix’s famous culture deck. They didn’t just talk about “freedom and responsibility,” they designed systems that made it real. No vacation policy because they trusted people to manage their own time. No expense policy because they expected people to act in the company’s best interest. High performance standards because they believed people wanted to do great work.

The environment gave people permission to act like the responsible, capable adults they were.

Here’s the crucial insight: People don’t resist good environments; they resist being controlled within bad ones. When the environment is designed well, compliance becomes commitment. Rules become principles. Management becomes leadership.

The authority of example (Part 1) establishes trust. Environmental design (Part 2) scales that trust into systems that work even when you’re not in the room.

The Flourishing Formula

So how do you actually design environments for excellence? How do you create the conditions where eudaimonia becomes the natural state?

The Flourishing Formula has three dimensions: Physical Environment + Cultural Environment + Systems Environment = Conditions for Excellence.

Physical Environment: Space Shapes Behavior

Never underestimate the power of physical space to influence behavior and performance. Your environment sends constant signals about what’s valued, what’s expected, and what’s possible.

Open offices were supposed to increase collaboration, but they often create noise, distraction, and stress. Traditional cubicles were designed for efficiency, but they kill creativity and connection. The best physical environments are intentionally designed to support the specific behaviors and outcomes you want.

Pixar’s headquarters has a massive atrium that forces people from different departments to cross paths regularly. This “collision space” creates serendipitous connections that spark creative breakthroughs. That’s environmental design in action.

Google’s offices include spaces for focused work, collaborative brainstorming, and informal connection. They recognized that different types of work require different types of spaces, and they designed environments to support the full spectrum of human performance.

Your physical environment should make the right behaviors easier and the wrong behaviors harder.

Cultural Environment: Norms Drive Performance

Culture isn’t what you say; it’s what you reward, tolerate, and celebrate. It’s the unwritten rules about how things really work around here. And culture is shaped by thousands of small environmental cues that either reinforce or undermine your stated values.

If you say you value innovation but punish every failure, you’ve created a cultural environment that kills creativity. If you talk about work-life balance but send emails at midnight, you’ve signaled that availability matters more than results. If you claim to want collaboration but only reward individual achievements, you’ve designed a competitive environment.

Cultural environment is created through the accumulation of consistent signals over time.

The best leaders are obsessive about cultural design. They think carefully about what gets celebrated in meetings, what stories get told and retold, what behaviors get promoted, and what actions get ignored or discouraged.

At Patagonia, the cultural environment reinforces their mission at every level. They offer on-site childcare and flexible schedules because they believe in work-life integration. They encourage employees to take time off for environmental activism because they want people who care about the planet. They measure success not just by financial metrics but by environmental impact.

The cultural environment gives people permission to bring their whole selves to work in service of something bigger.

Systems Environment: Processes Enable Excellence

This is where most organizations fail. They have good intentions and even good culture, but their systems and processes are designed for mediocrity, compliance, and risk avoidance rather than excellence, innovation, and growth.

Your systems environment includes everything from how decisions get made to how information flows, from how performance gets measured to how conflicts get resolved. These systems either enable excellence or constrain it.

Consider how different companies handle expense reports. Some require multiple approvals, detailed receipts, and lengthy justifications for every purchase. The system signals distrust and creates bureaucratic friction. Others give people spending guidelines and trust them to use good judgment. The system signals respect and enables speed.

Your systems should be designed to make excellence the path of least resistance.

The most powerful systems environments create feedback loops that naturally drive improvement. They make problems visible quickly, enable rapid experimentation, and reward learning over perfection.

Amazon’s “Day 1” mentality isn’t just a philosophy; it’s built into their systems. They have mechanisms for maintaining startup speed and agility even at massive scale. Their decision-making processes, performance metrics, and organizational structures all reinforce the Day 1 mindset.

When all three dimensions align, physical + cultural + systems, you create an environment where excellence becomes inevitable.

The Environmental Leadership Framework

Here’s the systematic approach for creating environments where excellence thrives: Assess, Design, Implement, Iterate, Scale.

Assess: Current Environmental Reality

Most leaders have never actually assessed their current environment objectively. They know their intentions, but they don’t know their impact. They focus on what they’re trying to create without honestly evaluating what they’ve actually built.

Start with brutal honesty about your current environmental reality.

Ask these questions:

- What behaviors does our current environment actually reward?

- What messages do our physical spaces send about what we value?

- What do our systems make easy, and what do they make difficult?

- If someone spent a week observing our organization, what would they conclude about our real priorities?

Get input from people at different levels and functions. The view from the executive suite is often very different from the view from the front lines. What feels empowering to leadership might feel constraining to individual contributors.

The gap between intended environment and actual environment is where your leadership work begins.

Design: Intentional Creation of Conditions

Once you understand your current reality, you can begin intentional design. This isn’t about copying what works somewhere else; it’s about creating the specific conditions that will enable excellence in your unique context.

Start with the end in mind: What behaviors and outcomes do you want to see more of?

If you want more innovation, design environments that make experimentation safe and learning visible. If you want better collaboration, create systems that require cross-functional cooperation to succeed. If you want higher quality, build feedback loops that catch problems early and celebrate excellence.

The key is to think systemically. Don’t just change one element; consider how physical space, cultural norms, and operational systems can work together to reinforce the behaviors you want.

Design with the understanding that people will naturally optimize for whatever you measure and reward.

Implement: Systematic Rollout with Feedback

Environmental change is like turning a large ship, it takes time, consistency, and constant course correction. You can’t just announce new values and expect immediate transformation.

Implementation requires patience, persistence, and continuous communication about why the changes matter.

Start with pilot programs where you can test and refine your environmental design. Get feedback from the people who will be living in the new environment. Be willing to adjust based on what you learn.

Most importantly, model the behaviors you want to see. If you want an environment of psychological safety, you need to demonstrate vulnerability and admit your own mistakes. If you want a culture of continuous learning, you need to be visibly learning and growing yourself.

Your personal behavior is part of the environmental design.

Iterate: Continuous Improvement Based on Results

No environment is perfect from the start. The best leaders treat environmental design as an ongoing experiment, constantly gathering data about what’s working and what isn’t.

Create feedback mechanisms that help you understand the real impact of your environmental choices.

This means looking beyond surface metrics to understand deeper patterns. Are people actually collaborating more, or are they just attending more meetings? Is innovation increasing, or are people just talking about innovation more? Are you creating psychological safety, or are people just being more polite?

The goal is continuous improvement toward conditions that better enable human flourishing and organizational excellence.

Scale: Expanding Successful Environments

Once you’ve proven that your environmental design works in one context, the challenge becomes scaling it across larger systems without losing its effectiveness.

Scaling environmental design requires understanding principles, not just copying practices.

What works in a 20-person startup might not work in a 2,000-person corporation. What works in one culture might not work in another. The key is to understand the underlying principles that make your environment effective and adapt them to different contexts.

The most successful environmental leaders become teachers, helping others create their own versions of excellence-enabling environments.

Practical Application: Your Environmental Leadership Audit

Let’s get practical. Here’s how you can start applying environmental leadership principles immediately, regardless of your formal position or authority.

Start with your sphere of influence. You might not control the entire organization, but you control your team, your projects, your meetings, your workspace. Begin there.

Physical Environment Audit

- What messages does your workspace send about priorities and values?

- How does the physical setup enable or constrain the work you want people to do?

- What simple changes could you make to better support focus, collaboration, or creativity?

Cultural Environment Audit

- What behaviors get celebrated, ignored, or discouraged in your sphere?

- What stories get told and retold about success and failure?

- How do you respond when people take risks, make mistakes, or challenge assumptions?

Systems Environment Audit

- What do your current processes make easy or difficult?

- How do decisions get made, and how quickly can you adapt when you learn something new?

- What gets measured, and how do those metrics influence behavior?

Remember: You don’t need permission to start creating better environments within your sphere of influence.

The beautiful thing about environmental leadership is that it’s contagious. When people experience a well-designed environment, they want to create similar conditions for others. Excellence spreads through environmental design.

Leading by Creating

Here’s what I want you to understand: The ultimate leadership leverage isn’t controlling people; it’s creating conditions where they naturally excel.

This connects directly to the authority of example we explored in Part 1. Character-based authority establishes trust. Environmental design scales that trust into systems that work even when you’re not present.

When you combine the authority of example with environmental design, you create leadership that multiplies itself.

People don’t just follow you; they internalize the principles and create similar environments wherever they go. Your influence becomes self-replicating because it’s built into how people think about creating conditions for excellence.

This is arete in action, excellence that reproduces itself through intentional design rather than accidental circumstance. It’s leadership that serves human flourishing (eudaimonia) by creating environments where people can express their highest potential.

The leaders who master environmental design don’t just achieve better results; they create better humans.

They understand that their ultimate responsibility isn’t to control outcomes but to create conditions where the right outcomes become inevitable. They focus on designing systems that bring out people’s best instincts rather than trying to manage their worst ones.

This is the second principle of Leadership Through Being: Great leaders don’t manage people; they design environments where people naturally manage themselves toward excellence.

The authority flows not from what you demand but from what you create. The influence comes not from what you control but from what you enable. The legacy isn’t what you accomplish personally but what you make possible for others.

Environmental leadership is how you scale character into systems that outlast your tenure and multiply your impact.

Final Thought

The ancient Greeks understood that eudaimonia (flourishing) wasn’t an accident, it was the result of intentional design. Environmental leadership is the modern application of this timeless wisdom: creating the conditions where human beings naturally express their highest potential. When we shift from trying to control people to designing environments that enable their excellence, we discover the ultimate leadership leverage. True arete (excellence) emerges not from what we demand, but from what we make possible. The greatest leaders don’t just achieve results; they create the conditions where extraordinary results become inevitable.

What environment are you creating? How are your current systems, spaces, and cultural norms enabling or constraining the excellence you want to see? The opportunity to lead through environmental design is available to everyone, regardless of position or title.